Ralph Waldo Emerson's Wide World by Jillian Hess

Highlights

Make your own Bible. Select & Collect all those words & sentences that in all your reading have been to you like the blast of a trumpet out of Shakespear [sic], Seneca, Moses, John, & Paul.

Unlike his contemporaries, Emerson didn’t produce a single literary work to cement his fame

Emerson’s remarkable notebooks—263 of them remain, housed by Harvard’s Houghton Library

Emerson began his lifelong habit of keeping regular journals in January of 1820, during his Junior year at Harvard College. He titled this inaugural collection “The Wide World”—a name he would use for the next four years, filling thirteen editions. After that, he moved on to designating his notebooks with roman numerals and then alphabetic letters.

These pages are intended at their commencement to contain a record of new thoughts (when they occur); for a receptacle of all the old ideas that partial but peculiar peelings at antiquity can finish or furbish; for tablet to save the wear & tear of weak Memory & in short for all the various purposes & utility real or imaginary which are usually comprehended under that comprehensive title Common Place book.

Emerson continues to muse that we write differently when just for ourselves, without the expectation of an outside audience.

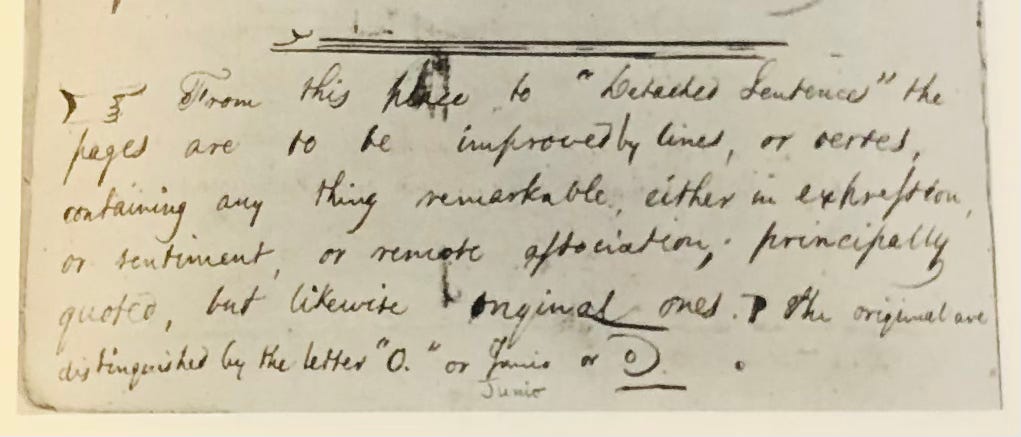

Emerson’s “Wide Worlds” contain quotations, but entries skew towards original content typical of a diary. For this reason, Emerson felt he needed his own symbol—a sign to differentiate his original ideas from those he borrowed.

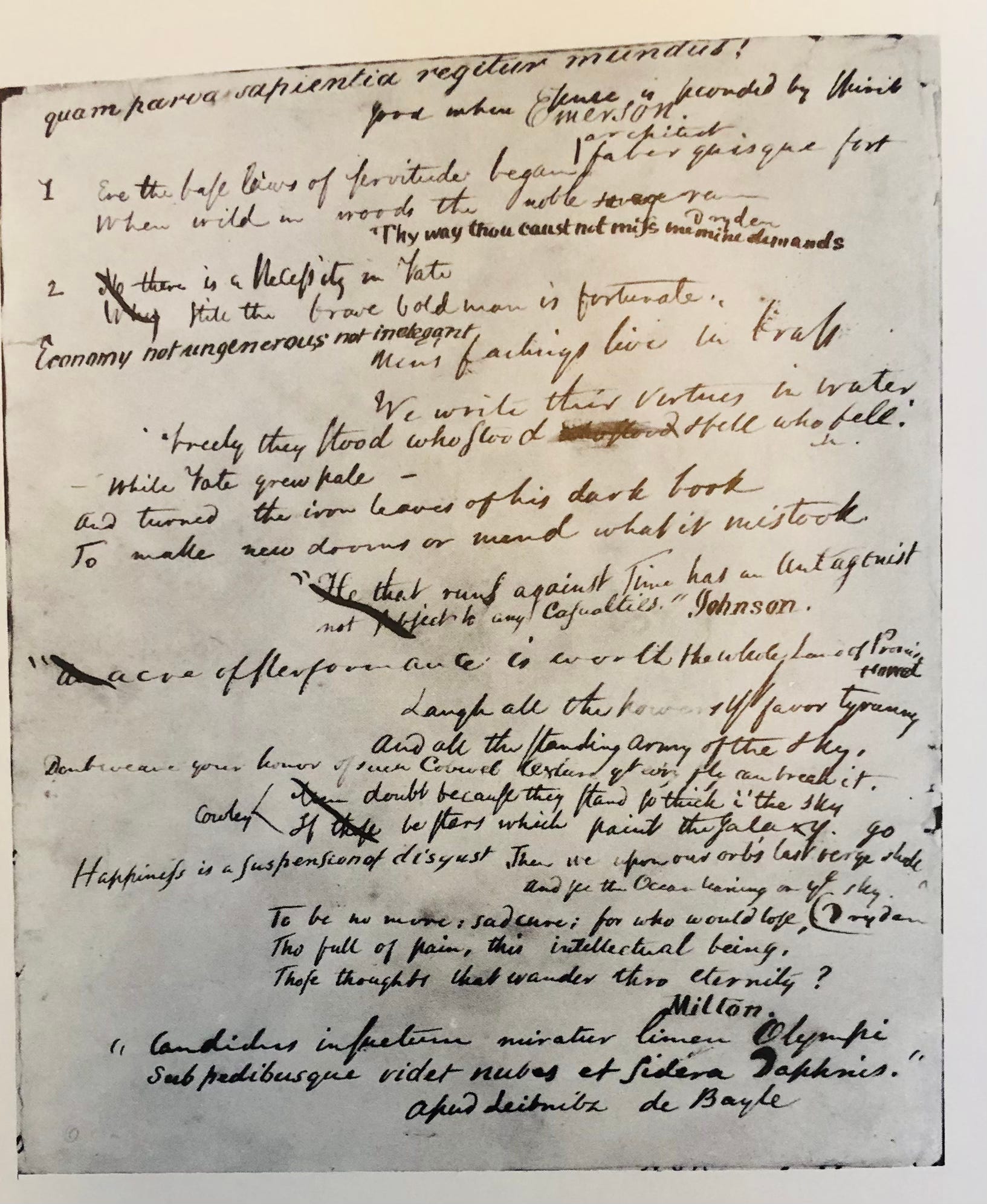

After a wonderful manicule (☞), Emerson directs himself to sort though his notes and improve lines that contain something “remarkable.” He explains that he will signal an original thought with “the letter ‘o’ or ‘Junio’” or the symbol you can see at the bottom of this image:

Emerson designed his notebooks as though they were printed books. Accordingly, he added prefatory material like epigraphs and dedications. But he doesn’t dedicate his notes to people, but to ideals.

He crossed out quotations as he used them in his own writing

Emerson delivered an entire lecture titled “Quotation and Originality,” praising the art of quotation.

Name your notebooks: the names we give our notebooks designate a relationship—sometimes aspirational—with literature and the world of ideas.

develop a symbol for your personal thoughts

When you recompose material in such a way that it becomes your own, you might as well designate it with your unique symbol.

Dedicate your pages to an ideal: We turn to our notebooks with hope—to remember quotations, to produce new writing, to document our lives. Perhaps a dedication page to focus that hope might be beneficial.

References

Hess, Jillian. “Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ‘Wide World.’” Noted, 23 Sept. 2024, https://jillianhess.substack.com/p/ralph-waldo-emersons-wide-world.